Thankful for the Internet

Hey, maybe you heard, maybe you didn’t, but Cloudflare broke this week. Now, one website being down wouldn’t be so bad, but this website happens to serve as the backend for a lot of other services that don’t work without it. It can be kind of scary to ponder how fragile the internet really is, so it’d be normal if you were worried. Or maybe you’re solutions-focused -- I know I can be. I was even reading a more productive take from a cybersecurity analyst for NPR that I really enjoyed.

I’m not here to suggest solutions or worry about an outage, even if that’s usually my purview. Rather, I’d like to take a minute to be grateful for the fact that, for most of my life, the internet has gone on spinning without a care or worry from me. Thanksgiving is right around the corner. Given the Holiday, I would like to explain why I’m very thankful for the internet. It’s hard to explain, but the little I know makes me to want to shout, “HEY! THIS IS PRETTY COOL!”

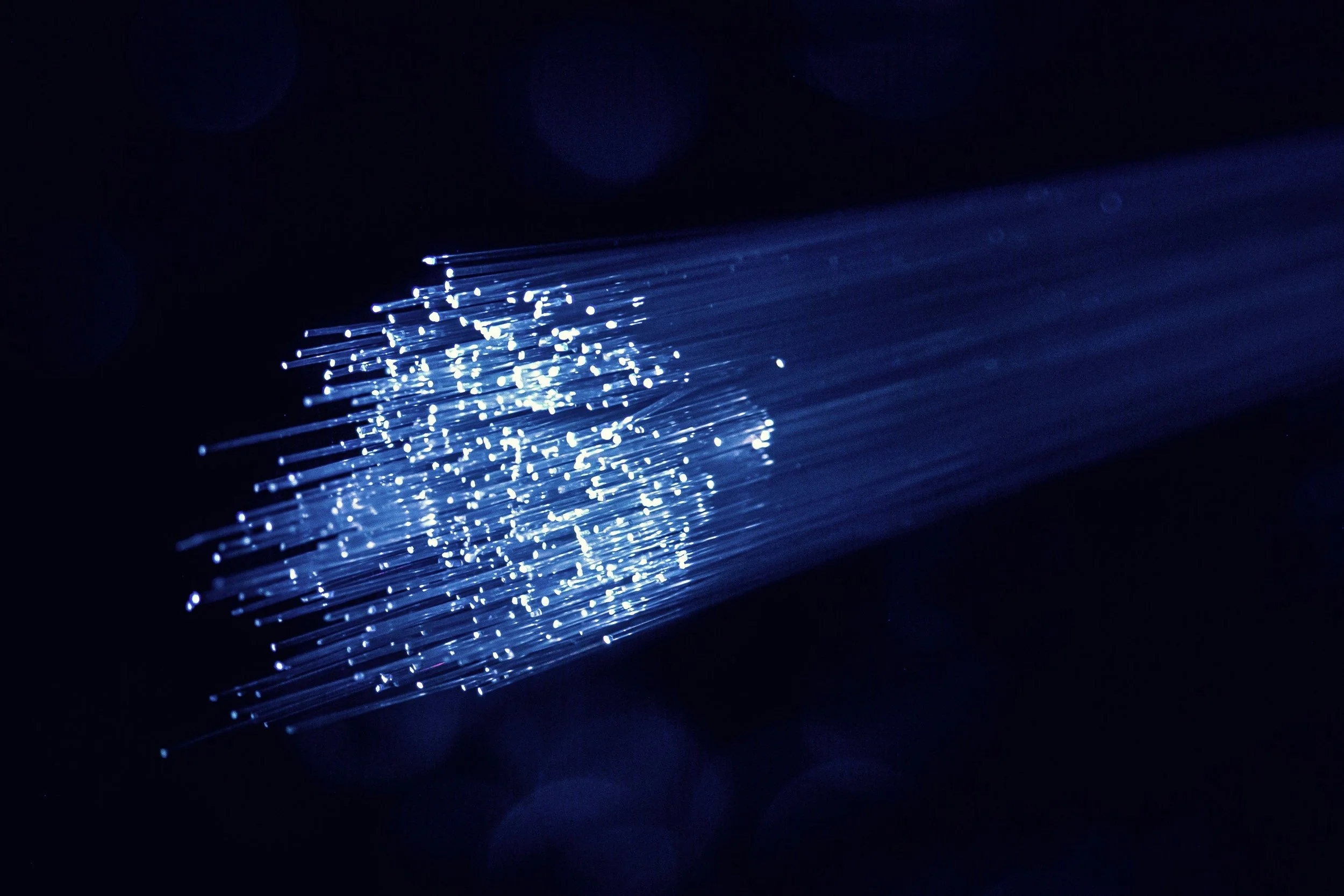

To do this thankful exploration of the internet, I’d like to explain just three things. The first component is the ‘inter’ part of the internet. The biggest gaps to close with communication on our humble planet happen to be giant, beautiful oceans. And while they are pretty hostile to technology, we have a super clever solution. Underneath the ocean, on fiber optic cables about the diameter of human hair, almost all international data traffic is happening. If you could scoop up all the water out of the ocean, you’d see these thin black lines running from London to New York, for instance. (Tragically you won’t see any birds propped up on them, and we’re heartbroken about it.)

So, with all that internet traffic swimming across the ocean, how the heck does your request get to the right place? That’s where IP addresses come in, describing where traffic is intended to go. Computers don’t speak English, they speak in Binary, which is made of numbers, not letters. Humans are much less amazing at reading and speaking in numbers, so we use a system called DNS (Domain Name System) to convert Google.com into numbers your computer can look up. So that’s part two of this equation: you type in a website or open an app, and your phone or computer turns those words into numbers, and the traffic is off to the races, headed to that numbered address. But what does the traffic look like? Ships? Motorcycles? No, they look like packages or packets.

That’s the third component. When you access a photo or video on the internet, you don’t access the whole thing. It’s chopped into tiny bits called packets in the thousands and hundreds of thousands and beamed across the world in seconds. These packets have address identifiers for where they are from and where they need to go and numbers, like 1 of 500. Your computer will check for all 500 packets when they arrive on your machine, and if it’s missing packet 48, it will reach out to ask for just for that missing one. Because packet sizes can vary and each person is different, it’s hard to say for sure, but you’ll probably send and receive at least 3 billion of those packets today alone (that’s 24.6 quintillion packets per day, assuming every human on Earth is utilizing roughly the same).

When I sit and think about that, I find myself much less worried and much more grateful that things like Cloudflare operate relatively without incident. I hope I’ve managed to convince you to be grateful that the marvel of the internet works as well as it does and with such cooperation. It’s hard to overstate just how powerful and wonderful a tool it is. I hope we don’t take it for granted.

Happy Thanksgiving !